"With immediate effect, no fees are payable for ET proceedings"

Blog

Gone is the demand on HM Courts & Tribunals Service's website for a fee when you submit a tribunal claim. Instead, a brand-new message appears: "with immediate effect, no fees are payable for ET proceedings".

It's not every day that a case comes along which results in such a big turnaround overnight. But yesterday was a big day for employment law. In fact, from the buzz in the media, the Supreme Court's decision in R (on the application of UNISON) v Lord Chancellor is probably one of the most momentous employment decisions of recent times. For example, if the removal of any ongoing requirement to pay tribunal fees moving forward was not significant enough, the Supreme Court ruled that the payment of fees has been unlawful since its introduction in 2013, with the result the government is now required to reimburse all fees which have been paid (some estimates put the relevant figure to be repaid at £32 million).

This is all going to take quite some digesting. To help with this, I have given my thoughts on some of the questions arising out of the case, and for those of you wanting to know more, have included at the end of this post a more detailed analysis of the judgment.

Background

In 2013, the government introduced fees for Tribunal claims. It's basis for doing so was to: 1) help to transfer some of the cost burden from tax payers to those using the tribunal system; 2) incentivise early settlement; and 3) dis-incentivise those wishing to pursue weak or vexatious claims. The amount claimants were required to pay in the ET depended on the type of claim being brought – fees for type A claims (generally the simpler, lower value claims) were £390 in total and for type B claims (all other claims) were £1,200 in total. A limited fee remission scheme was available.

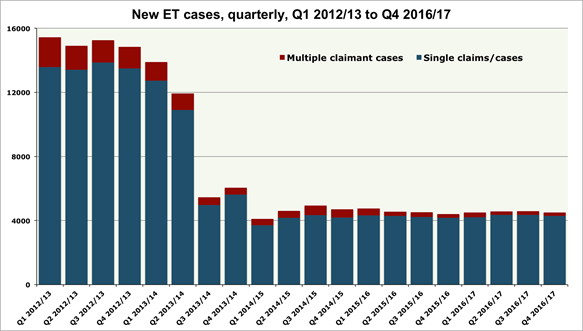

Unison first challenged the Lord Chancellor's decision to introduce fees before the fee regime even came into effect. Prior to yesterday's case, Unison lost in two High Court hearings and in the Court of Appeal. Our previous blog posts covering the stages of the judicial review proceedings can be found here. Unison's concerns were centred on the significant impact of tribunal fees – there has been a reduction of up to 70% in tribunal cases over the past three years. This chart gives a stark illustration of this:

[Graph courtesy of: https://labourpainsblog.com/2017/06/09/fees0617/]

The consequences of the judgment

Here are my immediate thoughts (and questions) on the consequences of yesterday's judgment:

The immediate consequence of the judgment is that fees are no longer payable on ET and EAT claims. It appears that the tribunal system is already busy trying to put processes in place to accommodate this change. However, work will inevitably be needed to rewrite tribunal rules, to ensure all forms and systems reflect the judgment and to make arrangements for the repayment of fees already paid.

It will be interesting to see if the removal of tribunal fees will have the same (albeit opposite) impact on the number of tribunal claims as their introduction had. Some commentators are speculating that people have 'got out of the habit' of bringing claims, but unfortunately I'm not convinced. This has the potential to spell unwelcome news for employers.

As referred to above, the Lord Chancellor has also already agreed to refund all fees previously paid. It is not clear at this stage exactly how the refund mechanism will work in practice or when refunds will be issued. Further, one would assume that refunds will be issued not only to claimants who have brought claims but also to respondents who have paid a claimant's fees as a result of an Tribunal Order being made (but what about respondents who paid fees as part of a settlement?). I predict an administrative headache for someone here!

There are also a lot of questions still unanswered...

For those claimants who were put off from bringing a claim as a result of the fees regime, will they have any recourse? Will tribunals allow them to make arguments that it was not previously reasonably practicable for them to bring a claim as a result of the fees regime? Will time limits be extended to now allow them to do so, notwithstanding the time limits imposed on employees bringing claims?

Longer term consequences will depend on whether the government chooses to consult on bringing in a new fee regime - whether that is by reducing the level of fee proposed, enhancing the remission scheme or requiring the employer to pay a fee for defending a claim. My feeling is that the Supreme Court's emphasis on people having "unimpeded access" to the courts and the unanimous nature of the decision will make this difficult for the government, particularly one facing the burden of Brexit with the slenderest of majorities. It is conceivable that the government might try to bring in a new fees regime via primary legislation, so that the courts could not strike it down again (the current regime was introduced using secondary legislation, which is why the courts could get involved). However, given the government's perilous grip on power, this seems unlikely. Have we seen the back of tribunal fees in their entirety?

The truth is only time will tell on all these questions (and no doubt many more) and the next few months will be interesting ones as the reverberations of this case are felt in full.

The Supreme Court's decision

The principal (and unanimously agreed) judgment of the Supreme Court was given by Lord Reed. In the judgment, Lord Reed first outlined the following key issues with the fees regime:

1) the majority of successful ET claims result in modest financial awards, with some claims not involving monetary awards, for example a claim for a written statements of particulars (paragraph 30 to 34);

2) the poor record of enforcement of ET awards (around 50% at most), including the additional cost of applying to the County Court for an execution order of £44 (paragraphs 35 to 37);

3) the significant impact on the number of claims being brought, as mentioned above (paragraphs 38 – 39);

4) fees are making a much less significant contribution to transferring the cost burden to users than had been expected (in the region of 13%) (paragraph 56);

5) there was no basis for concluding that only stronger cases were now being litigated (and that the regime was putting off vexatious litigants) (paragraph 57); and

6) the number of claims settled via Acas had actually decreased since the introduction of the fees regime, going from 33% in 2011/12 to 31% in 2014/2015, with legal commentators suggesting that some employers were delaying settlement negotiation to see whether a claimant would be prepared to pay the fee (paragraph 59).

Lord Reed then turned to whether the Fees Order was unlawful under English law, focussing on the constitutional right of access to the courts playing an inherent part to the rule of law. He stated that "the courts do not merely provide a public service like any other" and that in order for courts to perform their role "people must in principle have unimpeded access to them" (paragraphs 68 and 69). This is in stark contrast to the government's 2011 consultation paper focusing on the users of the system taking greater financial responsibility for the system itself. In considering whether the Fees Order prevented access to justice, Lord Reed concluded that the evidence before the court was that it did. He cited the clear reduction in the volume of claims as a result of the introduction of the fees regime: "The fall in the number of claims has in any event been so sharp, so substantial, and so sustained as to warrant the conclusion that a significant number of people who would otherwise have brought claims have found the fees to be unaffordable" (paragraph 91). He also concluded that fees should not just be affordable but reasonably affordable, and that if households on low to middle incomes had to sacrifice other ordinary and reasonable expenditure to bring a claim, this meant that fees could not be regarded as affordable. He also cited the example of the fees being set at a level which rendered it irrational or futile for claimants to bring some types of claims (for example those involving no monetary value) as demonstrating a clear impact on access to justice.

The second issue considered was whether the Fees Order could be justified as a necessary intrusion on the right of access to justice. He concluded that it could not, stating that the Ministry of Justice had provided no evidence to support why tribunal fees had been set at the level they had been. There had also been no evidence provided to demonstrate that the Fees Order incentivised early settlement or dis-incentivised those wishing to pursue weak or vexatious claims.

Finally, Lord Reed stated that the principle of effective judicial protection was a general principle of EU law (enshrined by Article 6 of the ECHR). EU case law has stated that the requirement to pay fees to civil courts must pursue a legitimate aim, and that there must be a reasonable relationship of proportionality between the means employed and the legitimate aim sought (paragraph 110). In light of his conclusions based on English common law, Lord Reed concluded that the Fees Order imposed disproportionate restrictions for the purposes of EU law (paragraph 117).

Lord Reed therefore concluded that the Fees Order was unlawful under both domestic and EU law because it prevented access to justice. As of yesterday, the Fees Order was immediately quashed.

Separately, Lady Hale also went on to consider whether the charging of higher fees for certain types of claims, including discrimination claims, was indirectly discriminatory (in that it put those with a protected characteristic at a particular disadvantage). Lady Hale's short separate judgment looked at whether the charging of higher fees or certain types of claims (type B claims) could be shown to be a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. The reality is that this analysis was a somewhat artificial exercise, given that the Supreme Court had held that the whole Fees Order could not be justified and was unlawful. However, Lady Hale concluded that there was no correlation between the higher fee charged for a type B claim and the merit of the case or the conduct of the proceedings by the claimant or on the incentives to reach settlement. She also stated that it had not been shown by the Ministry of Justice that the higher fee charged for a type B claim was more effective in transferring the cost of the service from taxpayers to tribunal users. She therefore concluded that charging higher fees for type B claims was not a proportionate means of achieving the stated aims of the fees regime.

Yesterday's decision has given a lot of people a lot of food for thought. As ever, if we can help in any way with your concerns, please get in touch.