SDLT and rural property – where did it all go wrong?

Insight

Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) is still a relatively new tax; its seventeenth birthday is later this year. Whilst many would agree that it is largely an improvement over its stamp duty predecessor, SDLT has developed a whole catalogue of its own issues, as many teenagers are liable to do.

How then did a tax that was intended to be accessible and straightforward become so complicated? More practically, what are the main SDLT issues facing rural estates and what can be done to navigate around these?

Where did it all go wrong?

In 2003, not long before SDLT was introduced, the Parliamentary Select Committee on Economic Affairs heard that:

“accessibility has been a long-standing problem with stamp duty. SDLT is a vast improvement – it will be easily understood by both professionals and the public…”.

With the benefit of hindsight, that ambition now seems naïve (to put it mildly) but SDLT did start its life as a largely straightforward and accessible tax for most rural landowners and property professionals.

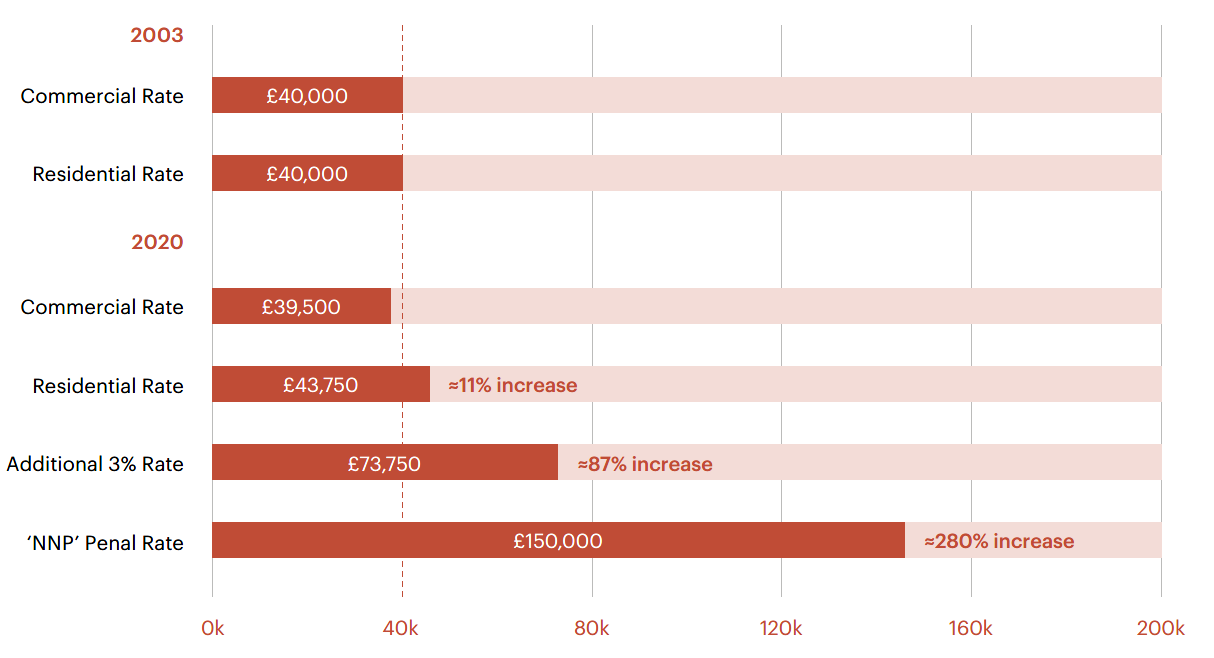

Take the example of a property purchased for £1m just after SDLT was introduced in 2003. The purchaser’s conveyancer or agent would have checked the relevant tax rates and rightly deduced that the purchaser should pay £40,000 of SDLT. The purchaser’s circumstances did not influence the tax payable and nor did the nature of the property in the vast majority of cases. There was not much need for detailed analysis of some of the terminology in the legislation as there were no real tax consequences.

If that same purchaser was to make another £1m purchase in 2020, the SDLT payable would depend on a huge range of nuanced factors that were mostly irrelevant in 2003. Depending on how these factors turn, the purchaser may now be liable for tax at any one of five different tax rates, or six if the purchase price was low enough for first-time buyer rates (and soon to be seven with the introduction of the new non-resident surcharge described below).

The difference in the tax currently payable on a £1m purchase is as much as £110,500, with the highest rates being around 280 per cent more expensive than the lowest. The amount of tax payable can now turn on the meaning of terminology in SDLT legislation that was never designed to be analysed in such detail. The slightest variation in the factual matrix can now have a huge impact on the tax payable and, of course, the potential liability of professionals.

Comparison of SDLT rates for a £1m property

Where are the main problem areas?

The factor which most influences the tax cost for many rural purchases is often whether the property is residential or not for SDLT.

In some cases, this is an easy call to make – compare a commercial farm building to a farmhouse or manor house for example. But the distinction between residential and non-residential (or mixed use) properties can be far less clear in many cases, particularly in the context of rural land.

Take, for example, a property consisting of a farmhouse with a self-contained annexe, woodland, paddocks and some grazing land. The SDLT treatment of such a property can differ significantly from one purchase to the next, depending on its exact makeup and use at the time of completion. Each case turns on its own facts, but it is important to remember that as a general principle, a property is only residential for SDLT where it consists entirely of dwellings and their accompanying land. Fields let on farm business tenancies and genuine commercial grazing licences to third parties can often indicate that the land is mixed use or non-residential, potentially leading to a significant SDLT saving.

Unfortunately, the mischief of SDLT legislation is not limited to the distinction between residential and non-residential property. As many rural estates professionals will know, the SDLT cost of acquiring property now also depends on a range of other factors too, including:

- the number of dwellings being acquired (multiple dwellings relief can sometimes reduce the SDLT payable).

- whether the purchaser and any spouse/civil partner owns any other properties (which can add an additional 3 per cent to the SDLT rate).

- the legal character of the purchaser as an individual, partnership, trust or company (‘Non-Natural Persons’ such as companies can be liable to a penal flat SDLT rate of 15 per cent and only individuals are eligible for the lowest residential SDLT rates, so it will rarely make sense to acquire residential property in a corporate vehicle except for a genuine commercial enterprise).

And that is all before getting to the fearsome scope of SDLT’s dedicated anti-avoidance rule (known as section 75A).

Solutions?

HMRC does recognise the complexity of today’s SDLT system and many of the shortcomings of the legislation; they have to wrestle with the same system after all. However, there do not seem to be any plans on the horizon to simplify SDLT. On the contrary, the latest developments suggest the system will become yet more complicated.

To give one example, HMRC has introduced a new dedicated clearance process for purchasers to obtain HMRC’s view on whether the SDLT anti-avoidance rule would apply to them before they make a purchase. That is welcome in principle, but in practice many of HMRC’s responses to clearance applications so far have been unhelpful in some cases and just plain wrong in others. As a result, purchasers are often driven away from engaging with HMRC and instead fall back on specialist professional advice, which does of course come at a cost.

The introduction of a new surcharge for non-residents, anticipated in April 2021, seems set to further complicate the position. Whilst the finer detail on these rates is still awaited, they are expected to impose a further 2 per cent surcharge in addition to current rates for all non-resident buyers (whether individual, trust, company or partnership). The government’s consultation on the surcharge suggests that a person’s residence for these SDLT purposes will be determined by yet another new set of rules entirely separate from the UK’s existing tax residence tests, placing a further burden on advisers and further costs on affected buyers.

If there is a silver lining for those looking to acquire rural property, it is that dedicated professional expertise has developed in tandem with the increasing complexity of SDLT. With the right advice, there are opportunities to make significant SDLT savings on certain purchases and to mitigate risks in uncertain cases.

If you require further information about anything covered in this briefing, please contact James Bromley, or your usual contact at the firm on +44 (0)20 3375 7000.

This publication is a general summary of the law. It should not replace legal advice tailored to your specific circumstances.

© Farrer & Co LLP, May 2020