Statutory residence test – the practical issues

Insight

An individual’s UK tax residence is determined by the statutory residence test (SRT) which has been in force since 6 April 2013. Before this date, UK residence was based on principles that developed from case law with certain statutory modifications. The newer codified test for residence generally enables greater clarity for many individuals, though in practice there are situations where the detailed mechanisms within the SRT do not apply easily to individuals’ circumstances and this can give rise to unusual results.

In this briefing, we summarise the mechanics of the SRT and highlight some practical issues in relation to the rules.

How does the SRT work?

There are three parts to the SRT as follows:

1. Automatic overseas test

An individual (P) is not resident for a tax year if P:

- was not UK resident in any of the previous three tax years and spends fewer than 46 days in the UK in the relevant year; or

- was UK resident in one or more of the previous three tax years and spends fewer than 16 days in the UK in the relevant tax year; or

- carries out full-time work abroad.

Key definitions

Day spent in the UK: A day where an individual is here at midnight. However, a day when P arrives in the UK as a passenger, leaves the following day and in the meantime undertakes activities related only to passage through the UK, will not be included. In addition, days spent in the UK due to exceptional circumstances beyond an individual's control that prevent the person leaving the UK do not count for the purposes of the SRT, provided they do not exceed 60 days. There is an anti-avoidance rule to prevent abuse of the midnight test for certain individuals who are in the UK but not present here at midnight on more than 30 days in any tax year. Finally, note that this definition of "a day spent in the UK" applies for the purposes of the SRT generally, subject to certain exceptions (eg see the definition of "workday" below which is relevant to the full-time work tests and the sufficient ties test).

Work: both employed and self-employed work is included, but casual voluntary work is not. Tax-deductible business travel and training time that is work-related and paid for by an employer count as work.

Full-time work abroad:

- P undertakes an average of 35 hours work per week overseas for the relevant year (calculated using special rules);

- P is in the UK for fewer than 91 days in the relevant year;

- There are fewer than 31 UK workdays in the relevant year; and

- P has no significant break from overseas work (being a period of more than 30 days).

Workday: A day of more than three hours of work (irrespective of whether the individual was in the UK at midnight).

2. Automatic UK residence test

An individual who does not meet the automatic overseas test will be resident for a tax year if they:

- spend 183 days or more in the UK in the relevant year; or

- have a UK home; or

- work full-time in the UK.

Key definitions

UK home: This has a wide meaning and can include a vehicle, vessel or other structure but only living arrangements with a sufficient degree of permanence or stability will count as a home. Property used as a holiday home will not be caught, nor will property that is let commercially. A person can be treated as having a home even if they don’t own or rent the property themselves. Key factors when assessing the position will be whether the relevant place is both capable of being and is actually used as a home.

An individual will be caught by the automatic UK residence test if P has a home in the UK during the relevant tax year and:

- P is present here for a total of at least 30 days in the relevant year; and

- there is a period of 91 consecutive days (at least 30 days of which fall within the relevant tax year) during which P has that UK home and either no overseas home or one or more overseas homes in which P spends a total of less than 30 days in the relevant year.

An individual will be treated as present at the home for a day if P has been there for any length of time on that day (ie it is not necessary for P to be there at midnight for the day to be counted).

Full-time work in the UK:

-

P works full-time (ie an average of 35 hours work per week) in the UK for 365 days, at least part of which is within the relevant year (calculated using special rules);

-

P has no significant break from UK work (being a period of more than 30 days);

-

More than 75 per cent of P’s workdays in the 365 day period are UK workdays; and

-

There is at least one UK workday which falls within both the 365 day period and the relevant year.

3. Sufficient ties test

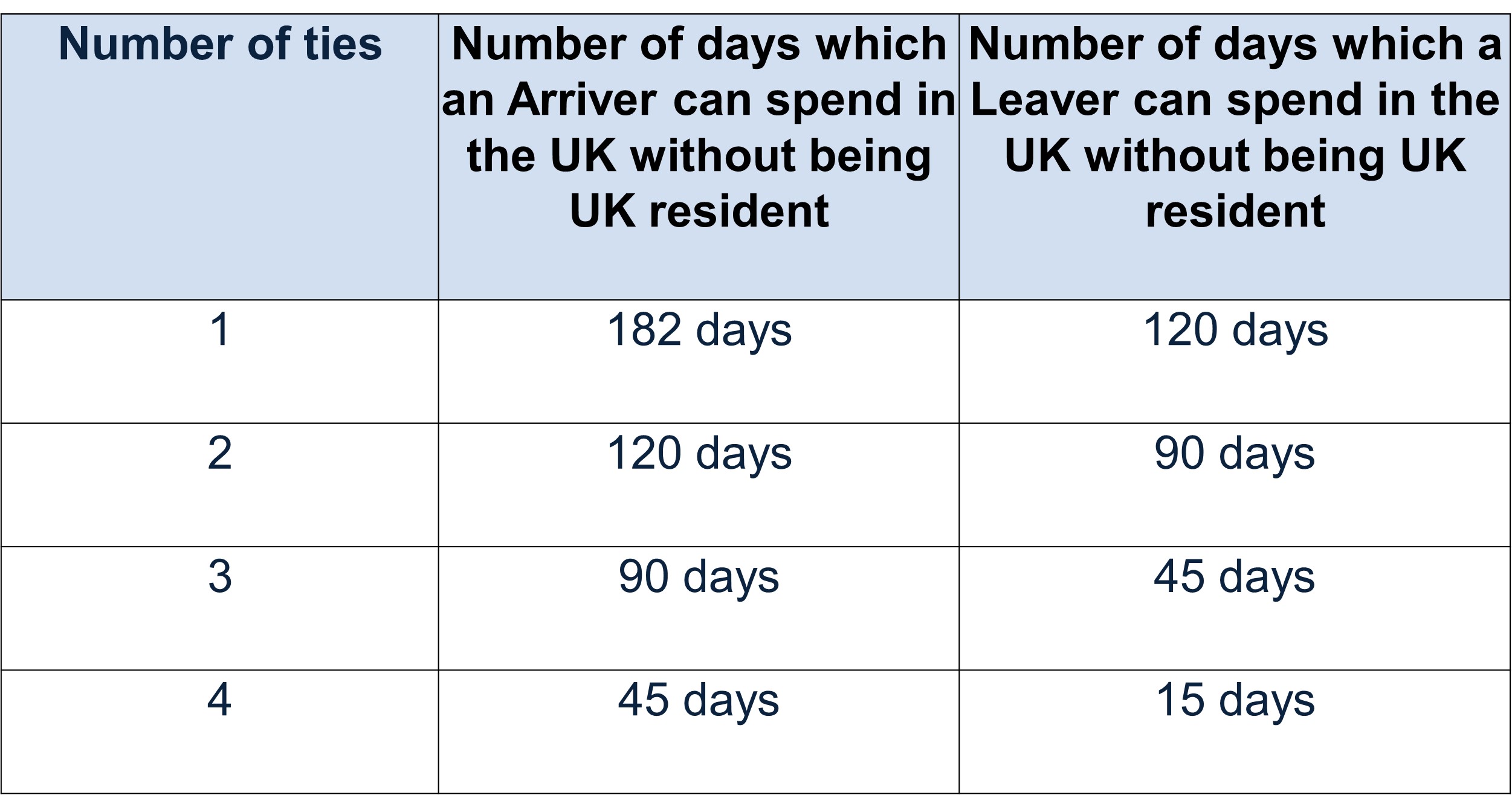

If an individual's residence status has not been ascertained under either of the above tests, this third test, which considers both the number of days spent in the UK as well as an individual's UK ties, will be applied. The test has been designed so that it is more difficult to relinquish UK residence status than to acquire it in the first place. Therefore, there are separate tests for:

Arrivers - defined as individuals not resident in any of the three previous tax years; and

Leavers - defined as individuals resident in one or more of the three previous tax years.

The test is structured so that the more UK ties that a person has, the fewer the days that can be spent in the UK without becoming resident (see the table below).

The following UK ties are relevant for both Arrivers and Leavers:

Family – the individual has a UK resident spouse, civil partner (or common law equivalent) or child under 18 years in the relevant tax year. It should be noted that:

-

a child does not represent a family tie if P sees the child in the UK for fewer than 61 days in total in the relevant year (a “day” here includes part days, as well as whole days, spent with the child); and

-

a child who is resident due to being in the UK for full-time education in the UK will not be treated as a family tie if that child spends fewer than 21 days in the UK outside term-time in the relevant year.

Note that if a family member’s residence depends on there being a “family tie” with the other, and vice versa, the family tie will be disregarded and will not count as a tie for either individual.

Accommodation – P has a place to live in the UK which is available to the individual for a continuous period of at least 91 days during the relevant year (although an interval of fewer than 16 days during which the accommodation is not available will be disregarded) and P spends at least one night there in that year. However, P is allowed to stay at the home of a close relative (which does not include a spouse or child under 18 years) for less than 16 nights without it being regarded as available accommodation. Note that accommodation can be "available" to an individual even if P is not the owner and UK holiday homes and temporary retreats are included in the definition. However, short stays at hotels will not usually constitute an accommodation tie.

Work - P works in the UK for a total of 40 days or more in the tax year for more than three hours a day.

90 days - P has spent more than 90 days in the UK in either or both of the previous two tax years.

Leavers also have the following additional UK tie:

Country – P spends more days in the UK than in any other single country in the relevant tax year.

Split-year treatment

The UK tax year runs from 6 April in one year to 5 April in the following year, and tax residence in the UK is assessed in relation to each tax year. If an individual comes to the UK or leaves the UK part way through a tax year, they risk being taxed as a UK resident for the whole tax year unless split-year treatment applies. This can be particularly important when implementing pre-arrival planning with a view to claiming the remittance basis of taxation.

Split-year treatment allows an individual to be treated as non-UK resident for part of the tax year. However, it does not apply in all circumstances and there are only limited routes by which an individual can qualify for split-year treatment:

Routes applicable when leaving the UK:

- full-time work overseas (or accompanying a spouse or partner who is working full-time overseas);

- leaving the UK to live abroad, moving one’s home there within six months of departure and not returning to the UK for more than 15 days for the rest of the relevant tax year;

Routes applicable when coming to the UK:

- coming to the UK to live here and having no other home outside the UK;

- working full-time in the UK;

- coming to the UK after leaving to work full-time abroad (or accompanying a spouse or partner in that position);

- acquiring a home in the UK and being resident in the UK in the next tax year.

Importantly, split-year treatment does not apply to all types of income and gains. Even where split-year treatment applies, certain income or gains received during the non-resident part of the year will be taxed as if the individual is UK resident for the full year.

Temporary non-residence rules

Individuals who leave the UK for only a few years can be caught by rules which impose additional tax on them when they return to the UK. The effect of the rules is that gains realised and certain types of income received while the individual was non-resident will be subject to UK tax on returning to the UK. These rules apply to people who (i) have been UK resident for four or more of the seven tax years prior to their last tax year of UK residence, and (ii) are then non-resident for five calendar years or less. Individuals, therefore, generally need to have six complete tax years of non-residence after a long period of UK residence to fall outside the rules.

Some practical tips

- Tax residence in the UK is unconnected to other concepts of residence (for example, the legal entitlement to be in the UK according to immigration law or “habitual residence” for family law and divorce purposes). This means an individual could be UK tax resident even if they have not established a legal basis on which they are able to remain here.

- Non-UK domiciled individuals intending to become UK tax resident for a period and claim the “remittance basis” of taxation should ideally take advice well in advance of moving to leave enough time to implement any pre-arrival planning. This can involve identifying suitable funds that can be brought to the UK tax-efficiently under the remittance basis. It can be most straightforward if such planning is done before 6 April in the year they intend to become UK tax resident, though, as noted above, split-year treatment can assist in some limited circumstances.

- Similarly, those wishing to leave the UK and relinquish UK tax residence should plan ahead, particularly individuals who have been working in the UK full-time but are intending to reduce their working hours abroad. This scenario can give rise to unusual results under the SRT because of the way the “full-time work in the UK” limb of the automatic UK residence test works and there is a risk the individual would be UK tax resident despite spending most of the tax year abroad.

- Individuals should keep good records of matters relevant to their UK residence. The self-assessment system in the UK means the onus is on individuals to correctly assess their position. In situations where individuals are close to the margins which would make them UK resident, good evidence is essential to defend any enquiry from HMRC.

- Record-keeping can be particularly important for people who spend some time working in the UK but want to avoid having a work tie (which would apply if they worked for more than three hours on any 40 days in the tax year). Work for many individuals is more fluid than traditional full-time employment, but the types of activities considered “work” for SRT purposes is broad and includes, for example, time spent on work-related emails, work-related travel that would be tax-deductible and job-related training time.

- How many “days” a person has spent in the UK for SRT purposes generally means how many days on which that person was present in the UK at midnight. For example, if an individual flew to the UK on 1 January and left on 7 January, they will have spent six “days” (ie midnights) in the UK for SRT purposes even though they were present in the UK on 7 separate days. In some circumstances, other days can also count as if the person was present here at midnight, including days on which the individual flew in and out of the UK on the same day and any other days when the individual was present in the UK at some part in the day but not at midnight (eg the 7th January day of departure in the above example).

- For those wanting to remain non-UK tax resident, even if an individual is within the relevant day limits according to the sufficient ties test, they need to ensure they do not fall within any of the automatic UK residence tests. This means ensuring that the individual:

- has at least one other home outside the UK and at least 30 days are spent there in the tax year (care needs to be taken in tax years where the overseas home is being sold); and

- has not been working in the UK full-time.

- has at least one other home outside the UK and at least 30 days are spent there in the tax year (care needs to be taken in tax years where the overseas home is being sold); and

- Care should be taken when assessing whether an individual has a "home" or "available accommodation" under the SRT. All relevant facts and conditions need to be taken into account and kept under review. Remember that even if an individual does not have a UK home they may still have an "accommodation tie" under the sufficient ties test if they have a place to live in the UK, the latter concept being more transient than a "home".

- If an individual has inadvertently become UK tax resident, the overall extent of UK taxation may be limited by the impact of double tax treaties.

If you require further information about anything covered in this blog, please contact Claire Randall, Ruth McKeown or your usual contact at the firm on +44 (0)20 3375 7000.

This publication is a general summary of the law. It should not replace legal advice tailored to your specific circumstances.

© Farrer & Co LLP, July 2022