New IICSA research into sexual abuse in residential schools – nine key findings

Insight

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (“IICSA” or “the Inquiry”) has published a 130-page research report into safeguarding children from sexual abuse in residential schools. They have also published a 15-page executive summary. This briefing summarises the report’s nine key findings.

Background

The Inquiry has received many accounts of sexual abuse taking place in schools, but considers children in residential schools to be particularly vulnerable to sexual abuse as a result of their isolation from their families and the involvement of staff in their intimate personal care.

IICSA seeks to explore how schools and other agencies respond to allegations of abuse by school staff and look at broader questions around school culture, governance, leadership, training and recruitment. IICSA’s Residential Schools Investigation was divided into two phases. Phase one focuses on closed, special and residential music schools (the public hearings in this phase closed in October last year). Phase two is a thematic investigation and the public hearings are currently scheduled for May 2020 (see our latest update here).

This latest research used a combination of information from interviews (with staff, pupils, parents and local authorities) and information about safeguarding incidents as recorded by the schools.

The report covers both “mainstream residential schools”, (defined by IICSA as state and private boarding schools, which are mainly mixed and many with day pupils as well as boarders) and “special residential schools”, which serve children with special education needs and disabilities. Fifteen schools participated in this research piece.

The research report looked at three main areas:

- how child sexual abuse in residential schools is understood from the perspective of staff, children, parents and local authorities;

- safeguarding practice in residential schools (ie prevention, identification, reporting and response); and

- views of staff, children and parents on good safeguarding practice.

It is important to note that this is a piece of research. It is not findings or recommendations from IICSA, although it is likely to considerably inform IICSA’s findings in the Residential Schools Investigation.

1. Within the education sector, residential schools face distinct and complex challenges to prevent and respond to incidents of child sexual abuse effectively.

The report identified a number of specific challenges or issues faced by residential schools, including:

- the need to balance independence and privacy with keeping children safe in a place which is both their home and school;

- the fact many of the children’s parents lived far from the school;

- the diverse range of cultures represented in schools potentially acting as a barrier to engagement with parents around safeguarding;

- a divergence in views (among schools and parents) about the proper level of access that children should have to mobiles (and other devices); and

- the potential for lines between professional boundaries to be blurred for staff in residential settings by virtue of acting “in loco parentis”.

2. All participants could identify “clear cut” types of child sexual abuse such as sexual violence and rape but were less confident about identifying and dealing with peer-on-peer concerns and other “grey areas”.

Staff and students were less confident about identifying and responding to conduct such as peer-on-peer abuse, relationships between children, and youth-produced sexual imagery. Many children expressed surprise that sharing or being shown sexualised images could constitute abuse.

These “grey-areas” require a sensitive assessment of the relationship between those involved and consideration of any cognitive impairment, communication needs or other contextual factors.

The report noted that it was parents, rather than children, that had the least inclusive and nuanced understanding of child sexual abuse.

3. Prevention work was multi-faceted and included awareness-raising, and education and training of staff, students and parents. This was both supported and underpinned by a strong “safeguarding culture” within schools.

Some schools reported a lack of consistency of safeguarding training for external support staff, but all schools delivered training to internal employees. Staff recognised that good training was a key part of prevention and felt that training could be improved by being more tailored and interactive, for example using case studies, and that opportunities for sharing learning / expertise should be taken.

Establishing an open and trusting relationship (within and between staff, pupils, and parents) was identified as key to helping prevent abuse and spot issues early.

Factors which supported an open culture included appropriate management of space in the school (restricting access to bedrooms and bathrooms, checking people in and out of communal spaces, for example) and having a zero-tolerance of sexualised, sexist or discriminatory language.

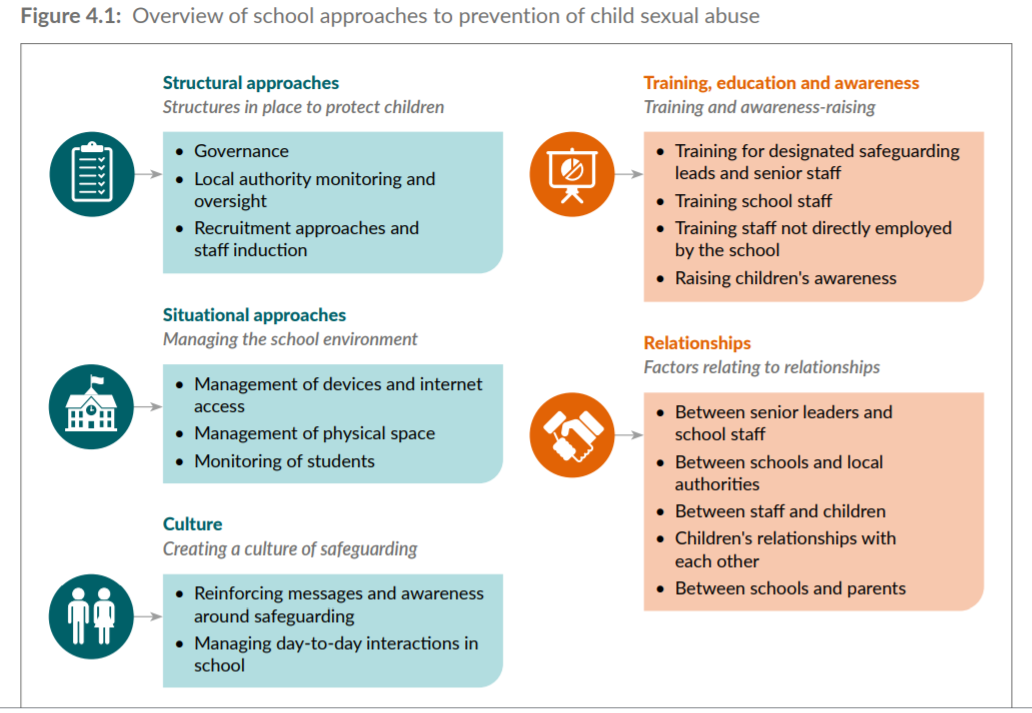

Figure 4.1 (seen below) is found on page 44 of the report, and shows the key components of schools’ approaches to prevention of child sexual abuse.

4. Parents and children wanted education and awareness-raising work within the school to start as early as possible. However, some parents were more “hands-off”, trusting the school to take the lead.

Education around sexual abuse (and related issues) could be challenging for SEND children.

Parents felt that schools should support children to learn how to use the internet safely, and children found safeguarding education more effective when it used repeated messages, informal discussions, and involved external speakers. Children valued approaches which dealt with issues around child sexual abuse directly.

Children thought they should be taught about safeguarding risks at an early stage, sessions should be tailored and age appropriate and cover a wider range of risks and models of abuse.

5. Disclosures were often initiated by children, suggesting that some children felt able and comfortable to talk about their concerns. Overall, staff reported the highest number of concerns.

Staff play a more active role in identifying signs of abuse in schools with children who have a high level of need.

Having staff (irrespective of role) that children trusted was an important part of encouraging children to report concerns. Other factors which impacted on when/whether children would report concerns included their consideration of their privacy, trust, accessibility, control and emotional factors (such as embarrassment or shame).

More girls reported concerns than boys, though boys logged online and peer-on-peer concerns as the most frequent issues.

6. Reporting practice varied between residential schools in the study, despite working from the same statutory guidance.

The report found a divergence in recording practices. Some schools, for example, spoke about identifying and responding to concerns that were not ultimately logged in a formal record, whereas some schools logged all concerns, even “niggling doubts” to help build a rounded view of a child and spot issues early.

7. Residential special schools recorded nearly 10 ten times the number of concerns per student than other residential schools.

It is not clear whether this is because staff are identifying and reporting a higher proportion of incidents or whether more concerns occur due to the level and type of need that some of the pupils in the special schools have.

8. Staff reported that they understood the guidance and knew what to do when incidents were raised. The use of discretion by safeguarding leads following up on concerns was important.

Staff were clear that concerns needed to be logged and reported to the designated safeguarding leads. Safeguarding leads exercised their professional judgement to decide how to respond to incidents, especially those described as “grey areas”. Staff reported the importance of being able to seek guidance from the local authority and/or the Police about cases they were not sure about, but expressed frustration that different authorities (and inspectors) have different ideas about when referral thresholds have been met.

A problem which was reported as being very relevant to residential schools was when a student’s family home was within a different local authority to the school. This created some confusion about which local authority should be contacted and which should lead in case management. Schools also struggled to find satisfactory responses for when students from overseas reported issues at home – schools reported challenges in contacting embassies and working with systems which did not have mechanisms to respond to concerns.

Schools offered support to those affected by an incident, carried out education with pupils afterwards, conducted risk assessments and worked with local authorities to share learning and expertise.

Schools reported that the general structure of safeguarding governance worked well, although there were sometimes challenges when a proprietor was distant from the school, where governors lacked experience in education / working with children, or where multi-academy trusts had trust boards as well as local governing bodies (thereby increasing the chance of issues “falling between the gaps”).

9. Schools reported difficulties escalating referrals to local authorities.

Schools expressed concerns about the lack of consistency and clarity around reporting thresholds for local authorities, and noted that some local authorities did not always have a full understanding of pupils and/or parents with cognitive impairments or intellectual disabilities. Schools also raised concerns about the amount of time it took local authorities to respond and the length of some investigations.

Local authorities said they worked hard to make their threshold information accessible and clear.

Conclusions

The report has touched on a number of themes that phase two of IICSA’s investigation will be covering. Phase two will be considering evidence and expert testimony about (among other things):

- the monitoring of children whose parents live overseas and the role of educational guardians in this context;

- mandatory reporting of sexual abuse;

- the adequacy of guidance around peer-on-peer abuse and sex and relationship education; and

- what factors contribute to a good or poor safeguarding culture in school.

We will need to see what recommendations the Inquiry makes in relation to the residential schools sector once phase two is complete. We expect the overall report to be published in early 2021. The Inquiry’s recommendations will draw on the evidence already gathered in phase one, the evidence and testimony to be collected in phase two, as well as the findings of this study.

Although we do not know what conclusions the Inquiry will draw, it is clear that as closed and self-sufficient communities (many in isolated rural areas), where students and staff live together, residential schools face unique and complex challenges. As a result they must ensure that safeguarding practice is in place around the clock, and their safeguarding arrangements must cover students’ study and leisure time, enable pupils to develop independence while staying safe, and be well tailored to respond to the specific challenges and risks that the residential environment creates.

It is also clear that residential school staff must play a greater role in identifying and responding to safeguarding issues, and must be alert to and well trained to deal with the particular risks and responsibilities that come with being “in loco parentis” to the students in their care.

If you require further information about anything covered in this briefing, please contact Maria Strauss, Sophia Coles, or your usual contact at the firm on +44 (0)20 3375 7000.

This publication is a general summary of the law. It should not replace legal advice tailored to your specific circumstances.

© Farrer & Co LLP, April 2020