Tackling online abuse: a look at the Online Harms White Paper

Insight

As the use of the internet and social media for abusive and dangerous purposes has increased, so has the call for internet giants like Google and Facebook to take greater responsibility for their services. In many ways, the law has failed to keep up with the speed of technological advances and, in some cases, the results have been devastating.

Last month the UK government launched a consultation into proposals to tackle illegal and harmful online content through a statutory duty of care to reduce ‘online harms’. In this article, we consider the implications of the government’s proposals for individuals dealing with online abuse or harassment.

When the murderous attacks on two Christchurch mosques were streamed on Facebook live in March this year, it marked for many an horrific nadir in the lawlessness of the internet. That its systems facilitated the streaming and then allowed 300,000 people to upload the video led to a torrent of criticism against Facebook, who confirmed they were ‘exploring’ content restrictions two weeks later. But this was not the first time that tech giants had been censured for their failure to address abusive content on their services.

Just one month earlier, Instagram announced it would ban graphic self-harm images in response to anger over the suicide of 14-year-old Molly Russell, who had accessed suicide-related material on Instagram shortly before her death. Last year, YouTube was condemned for failing to respond to the controversy caused by a vlogger who posted a video showing the body of an apparent suicide victim in Japan.

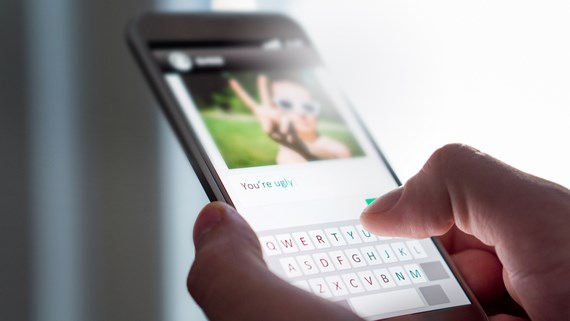

If the examples above represent the extreme, most of us have experienced some level of online harm, whether it be exposure to graphic content and hate speech or being on the receiving end of harassment and misinformation. For those who have tried to take action against this, securing an effective remedy can be difficult. Tech giants can take weeks, if not months, to respond to complaints, while online reporting tools can be limited and constraining, forcing users to explain a complex issue in 100 characters or report a viral video or tweet individually. And in many cases internet companies refuse to take action, encouraging complainants to contact users directly. This is of little use to individuals who are the subject of a targeted campaign of harassment.

While tech giants cannot control everything users do, there is an increasing sense that they could do more. The government’s response to these incidents, and to what many see as the failure of the tech giants to police their own back yard, is the Online Harms White Paper.

A new duty of care: the government’s proposal

The Online Harms White Paper proposes a new regulatory framework to ‘improve citizens’ safety online’. At the heart of the White Paper is the creation of a statutory duty of care requiring companies to take reasonable steps to keep users safe and tackle illegal and harmful activity on their services.

The new duty of care:

- covers both illegal and ‘harmful’ activity, from terrorist and extremist propaganda, child sexual exploitation and serious online violence to cyberbullying, anonymous abuse, harassment, intimidation and fake news

- requires companies to have effective and easy-to-access complaints tools for users, and to respond within an “appropriate timeframe’’

- will be enforced by an independent regulator that will introduce new codes of practice for compliance

- requires companies to take action in response to complaints in line with the regulator’s codes of practice

- requires companies to ‘go much further’ to prevent the spread of child sexual exploitation and other seriously offensive illegal content, and

- will be aimed at harms not addressed under existing legislation such as data protection law.

The government is currently consulting on the scope of this duty, but it is safe to assume that the new codes of practice will require tech giants to take a more active role in regulating user content on their services.

Crucially, internet companies will need to show that they are fulfilling the duty of care and the government insists the regulator will have a "suite of powers" to take action against those in breach. The government is consulting on a range of enforcement action including powers to:

- impose substantial fines

- render senior executives liable for their companies' failings

- disrupt a company’s business activities

- request transparency reports to demonstrate compliance, and

- block websites that are non-compliant.

The current consultation ends on 1 July 2019 and the measures above are bound to attract some criticism.

Who will have to comply?

The government’s proposals are not aimed exclusively at the likes of YouTube and Facebook, but cover any organisation allowing “users to share or discover user-generated content” or interact online. This includes messaging services like WhatsApp and smaller companies who provide hosting sites and web forums. However, the White Paper states that the initial focus will be on the tech giants who “pose the biggest and clearest risk of harm to users”, and that the regulator will take a “risk-based and proportionate” approach.

Shifting the burden

The White Paper is not without its detractors. The Adam Smith Institute has called it “an historic attack on freedom of speech…the most comprehensive online censorship regime in the democratic world”. In response, the government says the online regulator will not trespass on the freedom of the press or upon other regulators, such as IPSO or Ofcom.

Presently, if you find yourself the target of online abuse you may be able to rely on data protection, privacy, harassment, copyright or defamation law to get this content removed. The difficulty, however, is the speed with which tech companies respond as well as their approach to prolific or ongoing abuse, which is to require users to submit repeated complaints. The proposals put forward by the government in the White Paper could significantly lessen the burden on targeted individuals.

A question for the new regulator will be the extent to which companies need to take a proactive rather than reactive approach. Due to the EU’s e-Commerce Directive the government cannot require companies to undertake general monitoring, and most internet companies currently take the legal position that they are not responsible for content until it has been pointed out to them. However, the government’s new proposals could test this position, and the White Paper states that “there is a strong case for mandating specific monitoring” in cases where there is a threat to national security of the physical safety of children.

Key to the government’s proposal is its belief that “companies should invest in the development of safety technologies to reduce the burden on users to stay safe online”. The implication is that companies like Facebook and Google have more resources at their disposal than they are currently willing to throw at this problem. Balanced against this is the right to freedom of expression and the danger that companies adopt an overly cautious approach in order to minimise liability. Given the current state of affairs this seems unlikely, and hopefully the new regulatory framework will adopt a sensible approach.

If you require further information about anything covered in this briefing note, please contact Alicia Mendonca-Richards or Ed Perkins, or your usual contact at the firm on +44 (0)20 3375 7000.

This publication is a general summary of the law. It should not replace legal advice tailored to your specific circumstances.

© Farrer & Co LLP, May 2019